Evidence For Low Carb Diet

The science of low carb and keto

- Weight loss

- Metabolic risk factors

- Heart disease, cholesterol and saturated fats

- Diabetes type 2

- Diabetes type 1

- Safety

- Epilepsy

- Liver disease

- PCOS

- IBS

- Reflux disease

- Migraine

- ADHD

- Alzheimer's

- Parkinson's

- MS

- Fibromyalgia

- Intermittent fasting

- Environment

- Red meat

- Salt

- External resources

- For doctors

- Evidence policy

The page below summarizes the core scientific evidence behind low-carb and keto diets. Although these diets are still considered somewhat controversial by some health professionals, there is now high-quality evidence to support their routine use for weight loss and certain metabolic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and some forms of dyslipidemia. There is preliminary evidence for their use in other conditions as well.

Furthermore, evidence also suggests that natural saturated fats are neutral with regard to health, warnings about the health dangers of red meat are based on weak evidence with very low certainty, and low-fat diets do not appear to have any special health or weight benefits beyond those of a low-carb diet.1

.

Weight loss

- Meta-analyses

- RCTs

There is little evidence in the scientific literature that decisively indicates any particular diet is superior for helping people lose weight for more than two years. In fact, most people who use a diet to lose weight regain most or all of it.2 Yet with those caveats in place, on average, carbohydrate restriction outperforms low-fat and other diets for weight loss in studies that follow participants for up to two years.

Meta-analyses

A number of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), considered the strongest, most robust type of evidence, have come to the same conclusion: low-carb diets tend to outperform other diets for weight loss for up to two years.

Two examples show greater weight loss on low-carb diets compared to low-fat diets in studies that were from eight weeks to 24 months in length:

PLoS One 2015: Dietary intervention for overweight and obese adults: Comparison of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets. A meta-analysis [strong evidence] Learn more

The British Journal of Nutrition 2016: Effects of low-carbohydrate diets v. low-fat diets on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence] Learn more

Low carb does not just result in more weight loss than other comparison diets, it also results in more fat loss, especially when carbs are limited to 50 grams per day:

Obesity Reviews 2016: Impact of low-carbohydrate diet on body composition: meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies [strong evidence]

The limits of low fat

A 2015 article in the prestigious journal The Lancet summarizes all major low-fat weight loss scientific trials. The conclusion? There's no evidence that a low-fat diet helps people lose weight, compared to any other diet advice.

This should cause us to question the commonly held belief that a low-fat diet is right for most people. In fact, the meta-analyses mentioned above show that people tend to lose significantly more weight when they are given dietary advice that includes being allowed to eat fat to satiety.

The Lancet 2015: Effect of low-fat diet interventions versus other diet interventions on long-term weight change in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Weight loss and risk factors

A 2012 review of all major trials of low-carb diets show both reduced weight and improvement of the major risk factors for heart disease:

Obesity Reviews 2012: Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of the effects of low carbohydrate diets on cardiovascular risk factors [strong evidence]

RCTs showing significantly more weight loss with low-carb diets vs. other diets

There are at least 31 modern RCTs that show significantly better weight loss with low-carb diets, according to the latest count by the Public Health Collaboration UK. The number of studies showing the opposite? Zero.

Here are three of the best RCTs to date:

- New England Journal of Medicine 2008: Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet [moderate evidence]

This was a two-year trial in which 322 people were randomly assigned to follow a Mediterranean diet, a low-fat diet, or a low-carb diet. By the study's end, the low-carb group had lost the most weight, even though they were allowed to eat as much low-carb food as they needed to feel satisfied; the other two groups followed calorie-restricted diets.

- Annals of Internal Medicine 2014: Effects of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

In this one-year study, 148 people were randomized to consume a low-carb diet (less than 40 grams of carbohydrate per day) or a low-fat diet (less than 30% of energy from fat per day). In addition to losing 3.5 kg (7.7 lbs) more than the low-fat group, the low-carb group also had greater improvements in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), and other cardiovascular disease risk factors.

- Journal of the American Medical Association 2007: Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women. The A to Z weight loss study: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

One of the most well-known weight-loss trials (often referred to as the A to Z study) involved randomizing overweight premenopausal women to eat either a low-carb (Atkins), moderate-carb (Zone), low-fat (Ornish), or low-calorie, portion-controlled (LEARN) diet for one year. At the end of the study, the women in the low-carb group had lost twice as much weight (4.7 kg, or 10.3 lbs) as the Ornish and LEARN groups and nearly three times as much as the women in the Zone group.

Comment on RCTs

All of the studies above show significantly more weight loss for the group that was advised to eat a low-carb diet (the Atkins diet, in many cases). To the best of our knowledge, the opposite has never been shown: Low carb has never significantly lost a weight loss trial. This means that low carb's victory record over low-fat, calorie-restricted advice is 31-0.

Feel free to let us know of any exceptions (or more examples) by emailing andreas@dietdoctor.com.

Low-carb videos

Weight loss

How do low-carb diets work for weight loss? Learn more below.

-

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

-

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

Metabolic risk factors

Low-carb diets improve all the main features of metabolic syndrome: obesity, high blood sugar, high blood pressure, and a cholesterol profile that indicates metabolic dyslipidemia, which is characterized by low HDL and high TG.

Metabolic risk factors are strongly linked to chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, dementia, and even cancer.3 Because low-carb diets can improve risk factors related to these diseases, it may be an important tool in preventing their development.

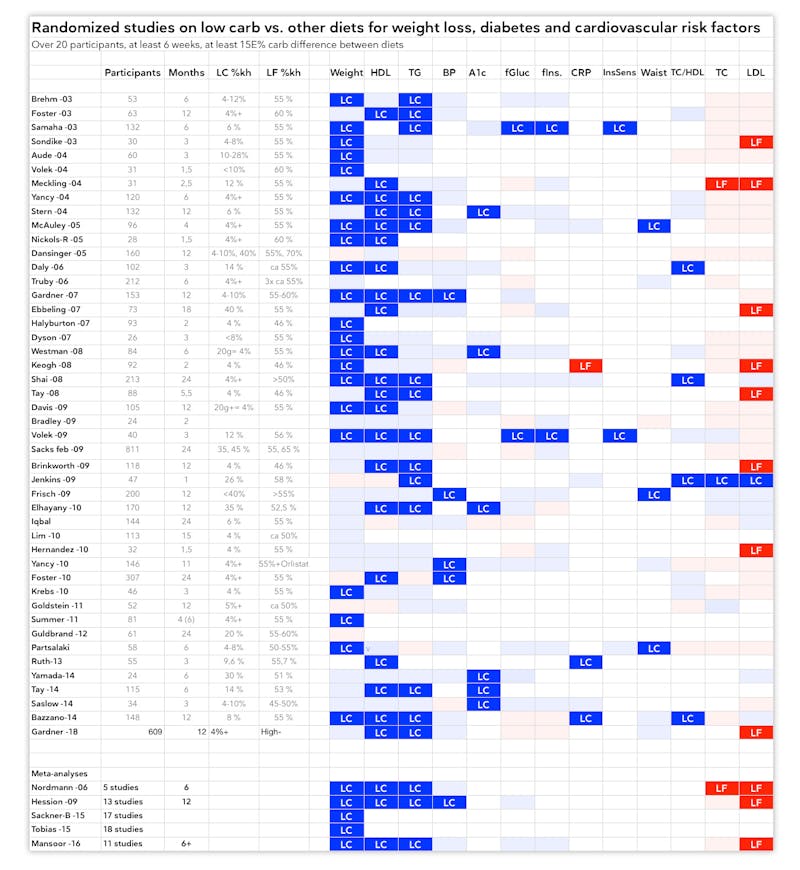

Overview of randomized controlled trials

The overview below of dozens of studies and meta-analyses comparing low-carb or low-fat diets shows that weight and other risk factors are more likely to be improved with a low-carb diet. The table shows studies up to 2018. More recent trials are listed individually after the table.

The blue (low-carb) or red (low-fat) squares signify a statistically significant advantage in improving the indicated risk factor. The pale blue or red squares signify a non-significant trend toward low carb or low fat being better.

As you can see above, low-carb diets outperform low-fat ones in improving all metabolic risk factors. On the other hand, low fat can result in somewhat lower total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.

However, ratios of cholesterol measurements that may have a higher predictive value than LDL, such as TG/HDL or TC/HDL ratios, also favor low carb because HDL and TG are more likely to be improved on a low-carb diet.4

In addition, low carb is more likely to improve other important risk factors: blood pressure, blood sugar, weight, and waist circumference, a measure of abdominal obesity.

Links to references

Here are links to all the studies above, ordered from oldest to newest:

Brehm -03, Foster -03, Samaha -03, Sondike -03, Aude -04, Volek -04, Meckling -04, Yancy -04, Stern -04, McAuley -05, Nickols-R -05, Dansinger -05, Daly -06, Truby -06, Gardner -07, Ebbeling -07, Halyburton -07, Dyson -07, Westman -08, Keogh -08, Shai -08, Tay -08, Davis -09, Bradley -09, Volek -09, Sacks -09, Brinkworth -09, Jenkins -09, Frisch -09, Elhayany -10, Iqbal -10, Lim -10, Hernandez -10, Yancy -10, Foster -10, Krebs -10, Goldstein -11, Summer -11, Guldbrand -12, Partsalaki -12, Ruth -13, Yamada -14, Saslow -14, Bazzano -14, Tay -15, Saslow -17, Gardner -18.

Meta-analyses

The effect of low-carb diets on the cholesterol profile is demonstrated in the following systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs showing improved HDL cholesterol and TG levels, as well as improved blood pressure:

Dong 2020. They evaluated 12 RCTs and found low-carb diets led to a decrease in TG and systolic BP and an increase in HDL.

PLoS One 2020: The effects of low-carbohydrate diets on cardiovascular risk factors: A meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Hellon 2019. They evaluated 8 RCTs concluding low-carb diets do not lead to a significant increase in LDL but did increase HDL and lower TG.

Nutrition Reviews 2019: Effects of carbohydrate-restricted diets on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Huntris 2017. They included 18 RCTs on low-carb diets and found improved HbA1c, TG and HDL.

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: The interpretation and effect of a low-carbohydrate diet in the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

Mansoor 2016. They evaluated 11 RCTs and found low carb led to greater weight loss, lower TG and higher HDL compared to low-fat diets.

British Journal of Nutrition 2016: Effects of low-carbohydrate diets v. low-fat diets on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

[systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Sackner 2015. They evaluated 17 trials of low carb vs. low fat and found better reduction in TG and systolic BP and increase in HDL for low-carb diets.

PLoS One 2015: Dietary Intervention for Overweight and Obese Adults: Comparison of Low-Carbohydrate and Low-Fat Diets. A Meta-Analysis [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Hession 2009. They reviewed 13 RCTs and found low carb better than low fat for HDL, TG and systolic BP.

Obesity Reviews 2009: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat/low-calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities

[systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Nordman 2006. They evaluated 5 RCTs of low-carb vs. low-fat diets. Low carb had better effects on TG and HDL.

Archives of Internal Medicine 2006: Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

[systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Heart disease, cholesterol and saturated fats

Despite half a century of research, there is still no high-quality evidence that natural saturated fat (from foods like butter and eggs) is anything but neutral from a health perspective.5

In a recent analysis, 19 leading researchers concluded that it's wrong to maintain the general advice to reduce saturated fat intake, as evidence does not support it.6 A similar article was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 7

Another recent analysis of the field published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine concluded that: "The preponderance of evidence indicates that low-fat diets that reduce serum cholesterol do not reduce cardiovascular events or mortality. Specifically, diets that replace saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat do not convincingly reduce cardiovascular events or mortality. These conclusions stand in contrast to current opinion." 8

Finally, a recent overview of the evidence linking saturated fat to heart disease, written by four prominent experts in the area, noted that when any fat, including saturated fat, replaces carbohydrate in the diet, there is improvement in important lipid markers related to risk of heart disease.9

A 2009 systematic review of cohort studies and RCTs looking at potential relationships between dietary factors and heart disease concluded that "Insufficient evidence of association is present for intake of … saturated or polyunsaturated fatty acids; total fat … meat, eggs and milk":

Archives of Internal Medicine 2009: A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease [moderate evidence]

Similarly, a 2010 review of cohort studies found "…no significant evidence for concluding that dietary saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of CHD or CVD":

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010: Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease [moderate evidence]

Meta-analyses of observational studies in 2015 and 2017 reached the same conclusions about the lack of association between saturated fat and heart disease:

British Medical Journal 2015: Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies [moderate evidence]

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017: Evidence from prospective cohort studies does not support current dietary fat guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis [moderate evidence]

The most recent systemic review of RCTs published in 2020 found eating less saturated fat was associated with a small reduction in cardiovascular events, but with no difference in risk of death. However, when analyzed based on cholesterol and study quality, any deleterious effect vanished.10

Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews 2020: Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Two other systematic reviews of RCTs, also showed no convincing evidence that saturated fat is harmful.

In these reviews, researchers concluded that replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats might slightly reduce the risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular events by about 14 to 19 percent.

However, in the first of these review, the reduction in risk was seen only in studies of at least two years duration and in studies of men, but not of women; furthermore, these changes appeared to have no effect on total or heart disease mortality:

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011: Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease [strong evidence]

In the second systematic review, for five of the eight studies analyzed there was insufficient evidence to conclude that the group outcomes were statistically significantly different from each other:

PloS Med 2010: Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

In addition, other more recent systematic reviews of RCTs haven't shown any reduction in heart diease risk as a result of substituting saturated fats with unsaturated fats:

Nutrition Journal 2017: The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: a meta-anlysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

Open Heart 2016: Evidence from randomised controlled trials does not support current dietary fat guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Annals of Internal Medicine 2014: Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

British Medical Journal 2013: Dietary fatty acids in the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression [strong evidence]

When it comes to butter and other high-fat dairy specifically, there is some observational evidence that people consuming it might be, if anything, thinner and healthier than others.

In 2012, researchers exploring the relationship between full-fat dairy, heart health, and weight concluded that "the observational evidence does not support the hypothesis that dairy fat or high-fat dairy foods contribute to obesity or cardiometabolic risk":

European Journal of Nutrition 2012: The relationship between high-fat dairy consumption and obesity, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease [weak evidence]

In fact, follow-up on the PURE study with over 177,000 subjects revealed no association between saturated fat intake and heart disease but did show saturated fat was linked to decreased risk for all-cause mortality and stroke. While this is weak observational data, it does make it much less likely that saturated fat in dairy is intrinsically harmful harmful

The Lancet 2017: Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study [very weak evidence]

The evidence above indicates that dietary advice to avoid fat in general and saturated fat in particular is based on a very weak scientific foundation.

Learn more: A user guide to saturated fat

Polyunsaturated fats and the Sydney Diet Heart Study

Advice to replace saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats – to reduce heart disease risk – is controversial, and the evidence supporting this guidance comes mostly from older studies with many weaknesses.

A re-evaluation of one of these, the Sydney Diet Heart Study, uncovered previously unpublished data showing a trend toward increased risk of death and heart disease in the group who got polyunsaturated omega-6 fats as a replacement for saturated fat in their diets.

When this data is included in a meta-analysis of other studies where saturated fats are replaced with polyunsaturated omega-6 fats, the almost-significant trend towards increased heart disease and death from heart disease shows that this replacement does not appear to have health benefits.

British Medical Journal 2013: Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Similar results were seen in the Minnesota Coronary Experiment, showing no health benefits to replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats.

BMJ 2016: Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73) [strong evidence]

However, there is much conflicting data ranging from mechanistic studies to RCTs. Read more in our evidence-based guide to vegetable oils.

The PURE study

A recent large observational study published in The Lancet shows that when diverse global populations are surveyed, diets with lower fat and higher carbohydrate content do not confer any health advantage.

The PURE study followed over 135,000 people in 18 countries from five continents for over seven years.

The researchers found that people who ate the most carbohydrate died earlier. A higher intake of fat, on the other hand, was linked to longer life, regardless of whether the fat was unsaturated or saturated.

This is an observational study and therefore cannot prove that eating fewer carbs and more fat extends life. However, it does call our current dietary advice into question, as the authors note: "Global dietary guidelines should be reconsidered in light of these findings." Learn more

The Lancet 2017: Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study [weak evidence]

DD Podcast interview with Prof. Andrew Mente, one of the co-authors of the PURE study

Hard endpoints on low carb

Most low-carb studies just track risk factors for heart disease. They are not large enough to track actual health outcomes, such as heart attacks. However one RCT tracked signs of carotid atherosclerosis during two years of advice to eat a low-carb, high-fat diet based on the Atkins diet. The study also followed participants eating low-fat and Mediterranean diets.

The result? There was significant regression of measurable carotid vessel wall volume seen in all three diet groups, implying a reduction of atherosclerosis. One possible explanation, according to the researchers, was the loss of weight and reduced blood pressure resulting from the change in diet.

What this tells us is that a higher-fat, lower-carb Atkins-type diet not only does not cause thickening of carotid arteries, it can help reduce signs of atherosclerosis.

Circulation 2010: Dietary intervention to reverse carotid atherosclerosis [moderate evidence]

Similarly, an 18-month RCT showed no difference in carotid IMT between a low-carb diet and a traditional diabetes diet for those with type 2 diabetes

PLos One 2020: Effect of a 90 g/day low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic control, small, dense low-density lipoprotein and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetic patients: An 18-month randomised controlled trial [moderate evidence]

In addition, a small non-randomized trial showed a keto diet can improve endothelial function based on flow-mediated dilatation (FMD). Although more data are needed for a stronger conclusion, this suggests keto diets may be beneficial for vascular health.

Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders Drug Targets 2020: Effects of a low carb diet and whey proteins on anthropometric, hematochemical and cardiovascular parameters in subjects with obesity. [non-randomized, weak evidence]

More

The Nutrition Coalition: The disputed science on saturated fats

Low-carb videos

Fats, cholesterol and dietary guidelines

What's wrong with our current carb-heavy official dietary recommendations, and their fear of natural saturated fats? Learn more below.

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

-

-

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

Type 2 diabetes

No improvements through conventional treatment

Conventional treatment, based on intensive medication regimens and the usual lifestyle advice to eat less and exercise more, has shown that, although it can help people manage type 2 diabetes, it does not ultimately improve their health outcomes. No less than seven randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that diabetes drugs do not help reduce heart disease, the major killer of people with diabetes.

On one occasion, a trial had to be stopped because the drugs meant to control blood sugar not only resulted in more weight gain and more adverse side effects, but also resulted in a greater risk of death.11

Low carb: systematic reviews

The advantage of a low-carb diet in type 2 diabetes has been recognized in several systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs:

BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 2017: Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes [strong evidence]

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018: Effects of low-carbohydrate- compared with low-fat-diet interventions on metabolic control in people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review including GRADE assessments [strong evidence]

Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism 2019: An evidence‐based approach to developing low‐carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: a systematic review of interventions and methods [strong evidence]

A meta-analysis from 2017 found that a low-carb diet resulted in reduced need for medication and improved health markers (HbA1c, HDL, TG, and blood pressure). The authors concluded that: "Reducing dietary carbohydrate may produce clinical improvements in the management of type 2 diabetes":

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: The interpretation and effect of a low-carbohydrate diet in the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

Another review of the evidence for low-carb diets in the treatment of type 2 diabetes, written by experts who are generally in favor of the idea, suggests that a low-carb diet should be offered as the first approach in managing type 2 diabetes:

Nutrition 2015: Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: critical review and evidence base [overview article]

Randomized trials

The following RCTs demonstrate the benefits of low-carbohydrate diets in people with type 2 diabetes:

PLos One 2020: Effect of a 90 g/day low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic control, small, dense low-density lipoprotein and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetic patients: An 18-month randomised controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Nutrients 2018: The effect of low-carbohydrate diet on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes [moderate evidence]

Nutrition & Diabetes 2017: Twelve-month outcomes of a randomized trial of a moderate-carbohydrate versus very low-carbohydrate diet in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes [moderate evidence]

Diabetes Care 2014: A very low-carbohydrate, low–saturated fat diet for type 2 diabetes management: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

Nutrition & Metabolism 2008: The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-glycemic index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus [moderate evidence]

Diabetic Medicine 2004: Short-term effects of severe dietary carbohydrate-restriction advice in type 2 diabetes–a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Non-randomized trials

A study of a ketogenic, low-carbohydrate diet done by Virta Health and involving about 330 people found that, at the one-year mark, 97 percent of the participants had reduced or stopped their insulin use. Furthermore, 58 percent no longer had a diabetes diagnosis; in other words, they had reversed their disease.12

These results indicate that type 2 diabetes is not inevitably progressive and irreversible. When low-carbohydrate diets are chosen by individuals and supported by healthcare professionals, type 2 diabetes can be reversed and potentially put into remission. Read more

Diabetes Therapy 2018: Effectiveness and safety of a novel care model for the management of type 2 diabetes at 1 year: an open-label, non-randomized, controlled study [weak evidence]

Frontiers in Endocrinology 2019: Long-term effects of a novel continuous remote care intervention including nutritional ketosis for the management of type 2 diabetes: A 2-year non-randomized clinical trial [weak evidence]

The longest published study yet on low carb for type 2 diabetes is a non-randomized intervention trial that compared a 20% carbohydrate diet (daily intake of carbohydrate was 80-90 grams) to usual care. Although the study was quite small, with only 23 participants in the final low-carb group, a follow-up assessment at 44 months showed continued improvement in HbA1c, weight, and reduction of diabetes medications:

Nutrition & Metabolism 2008: Low-carbohydrate diet in type 2 diabetes: stable improvement of bodyweight and glycemic control during 44 months follow-up [weak evidence]

In a 24-week interventional trial of people with obesity and type 2 diabetes who self-selected either a low-carb ketogenic diet or low-calorie diet, the ketogenic diet resulted in more weight loss and better glucose control:

Nutrition 2012: Effect of low-calorie versus low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet in type 2 diabetes [weak evidence]

Learn more: How to reverse type 2 diabetes

Prediabetes

A two-year Nonrandomized trial of a ketogenic diet run by Virta Health demonstrated blood sugar normalization in over 50% of participants with prediabetes.

Nutrients 2021: Type 2 Diabetes Prevention Focused on Normalization of Glycemia: A Two-Year Pilot Study [nonrandomized study, weak evidence]

Low-carb videos

Type 2 diabetes

To learn more about type 2 diabetes and low carb, have a look at one of these videos.

-

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

Type 1 diabetes

The authors of a recent systematic review of low-carbohydrate diets in type 1 diabetes concluded that there is an urgent need for additional randomized controlled trials and other high-quality studies in this area:

PLOS One 2018: Low-carbohydrate diets for type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review [moderate evidence] 13

Compared with the robust evidence base supporting low-carb and ketogenic diets for type 2 diabetes, research on carb restriction for type 1 diabetes is greatly lacking. However, as we await the results of RCTs currently in progress, the results from existing studies on low-carb diets in people with type 1 diabetes are encouraging.

Randomized trials

Controlled studies have shown that people with type 1 diabetes who limit carbs to 50 to 100 grams per day experience more stable blood sugar and fewer episodes of hypoglycemia compared to people with type 1 who eat higher-carb diets — with a bonus of increased weight loss in those who are overweight:

Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2019: Low versus high carbohydrate diet in type 1 diabetes: a 12-week randomized open-label crossover study [moderate evidence]

Learn more

Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2017: Short-term effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic variables and cardiovascular risk markers in patients with type 1 diabetes: a randomized open-label crossover trial [moderate evidence]

Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2016: A randomised trial of the feasibility of a low-carbohydrate diet vs standard carbohydrate counting in adults with type 1 diabetes taking body weight into account [moderate evidence]

Non-controlled studies

Some non-controlled studies, while considered weak evidence, demonstrate excellent "real world" results for people with type 1 diabetes who follow a low-carbohydrate diet long term.

This study shows that patients with type 1 diabetes who use a lower-carb, higher-protein diet achieve, on average, excellent results, with low rates of major complications. This study also shows that children who followed a carbohydrate-reduced diet did not show any signs of impaired growth, although the duration of time on diet was short (1.2 +/- 0.8 years).

Learn more

Pediatrics 2018: Management of type 1 diabetes with a very low–carbohydrate diet [weak evidence]

In addition, a group of Swedish doctors reported that their patients with type 1 who followed a low-carbohydrate diet consistently had significant improvements in blood sugar, HbA1c, and reduction in hypoglycemia after one year. These effects remained after four years in patients who stayed on the diet:

Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences 2005: A low-carbohydrate diet in type 1 diabetes: clinical experience – a brief report [weak evidence]

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome 2012: Low-carbohydrate diet in type 1 diabetes, long-term improvement and adherence: a clinical audit [weak evidence]

Learn more

Type 1 diabetes – how to control your blood sugar with fewer carbs

Low-carb videos

Type 1 diabetes

To learn more about type 1 diabetes and low carb, have a look at one of these videos.

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

MEMBERS ONLY

-

-

-

MEMBERS ONLY

Long-term safety of low carb

Some health experts have raised concerns about the long-term effects of low carb. All diets can be done well or poorly, and risk of of nutritional inadequacy exists with all ways of eating. However, a well-planned, nutritionally adequate low-carb diet has no evidence of risk, to the best of our knowledge, as carbohydrate is not a part of essential nutrition.

Bone health

Some concerns have been raised about the perceived risks of protein intake on the acid-base balance of the body and how that could affect bones. No evidence supports this concern. The internal pH of the body is firmly regulated and is not significantly affected by diet.14

Regarding bone health, the latest meta-analysis endorsed by the International Osteoporosis Foundation makes the situation very clear: "There is no evidence that diet-derived acid load is deleterious for bone health. Thus, insufficient dietary protein intakes may be a more severe problem than protein excess in the elderly."

Osteoporosis International 2018: Benefits and safety of dietary protein for bone health – an expert consensus paper [overview article]

A meta-analysis of RCTs and cohort studies concluded that higher protein intake isn't harmful for bone health and may even be beneficial for preventing bone loss:

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: Dietary protein and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation [moderate evidence]

Finally, three controlled trials show that low-carb is safe for bones, even when followed for up to two years:

Nutrition 2016: Long-term effects of a very-low-carbohydrate weight-loss diet and an isocaloric low-fat diet on bone health in obese adults [moderate evidence]

Annals of Internal Medicine 2010: Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Pediatrics 2010: Efficacy and safety of a high protein, low carbohydrate diet for weight loss in severely obese adolescents [moderate evidence]

The above supportive evidence is far stronger than evidence suggesting harm, as we detail in a news post about a study showing increased markers of bone turnover after 3 weeks on a keto diet on highly trained race walkers.

Learn more

Epilepsy

Ketogenic diets have been studied extensively in people with epilepsy. In fact, they are often recommended for those who either fail to respond to anti-seizure medications or can't tolerate their side effects.

A large review of 16 studies in adults with uncontrolled epilepsy found that ketogenic diets were well-tolerated long term and typically resulted in significantly fewer seizures or, in a minority of cases, complete freedom from seizures:

Epilepsia Open 2018: Ketogenic diet for treatment of intractable epilepsy in adults: A meta-analysis of observational studies [weak evidence]

RCTs have shown that ketogenic diets (including a less-strict version known as the modified Atkins diet, or MAD) are very effective for seizure control in some, although not all, children and adults with epilepsy:

Epilepsia 2018: Effect of modified Atkins diet in adults with drug-resistant focal epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2017: A randomized controlled trial of the ketogenic diet in refracatory childhood epilepsy [moderate evidence]

Epilepsy Research 2016: Evaluation of a simplified modified Atkins diet for use by parents with low levels of literacy in children with refractory epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Liver disease

Can low carb help reverse fatty liver disease? A team of Swedish researchers published a 2017 study in the journal Cell Metabolism that showed the effects of a low-carbohydrate diet with increased protein and no reduction in calories on obese subjects with fatty liver disease. The research plan was meant to separate the effects of caloric reduction and weight loss from those of carbohydrate restriction.

Lead author Jan Boren of the University of Gotheburg reported the effects of carbohydrate restriction on liver fat:

"We observed rapid and dramatic reductions of liver fat and other cardiometabolic risk factors and revealed hitherto unknown underlying molecular mechanisms."

Cell Metabolism 2017: An integrated understanding of the rapid metabolic benefits of a carbohydrate-restricted diet on hepatic steatosis in humans [weak evidence]

This effect was also shown in a more recent study:

JCI Insight 2019: Dietary carbohydrate restriction improves metabolic syndrome independent of weight loss [weak evidence]

These studies indicate that weight loss is not needed to improve the signs of NAFLD; the improvement appears to come from carbohydrate restriction alone. Although more research is needed in this area, earlier trials have also shown that low-carb and ketogenic diets may be beneficial for people with fatty liver disease:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2011: Short-term weight loss and hepatic triglyceride reduction: evidence of a metabolic advantage with dietary carbohydrate restriction [weak evidence]

Journal of Medicinal Food 2011: The effect of the Spanish ketogenic Mediterranean Diet on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot study [weak evidence]

Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U.S.A 2020: Effect of a ketogenic diet on hepatic steatosis and hepatic mitochondrial metabolism in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [nonrandomized study, weak evidence]

One RCT showed a Mediterranean keto diet was more effective than a low-fat diet for improving signs of fatty liver.

Journal of Hepatology: The beneficial effects of Mediterranean diet over low-fat diet may be mediated by decreasing hepatic fat content [moderate evidence]

And another RCT reported a keto diet is equivalent to a 5:2 intermittent fasting, and better than standard dietary advice for resolving fatty liver.

Journal of Hepatology Reports 2021: Treatment of NAFLD with intermittent calorie restriction or low-carb high-fat diet – a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

PCOS

Given the strong links between excess weight, high insulin levels, and other metabolic problems, a low-carb diet should be ideal for reversing polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). A low-carb diet consistently and reliably lowers insulin levels.15 This may indicate that low-carb diets can help reverse metabolic issues that include PCOS.

Although long term, high quality studies have not been done, and not all studies agree, much of the limited available science shows promise:

- One small 2005 study followed 11 women with PCOS as they went on a ketogenic low-carb diet for six months. The five women who completed the study lost weight, improved their hormonal status, and reduced the perceived amount of body hair. Two of them became pregnant despite previous infertility problems:

Nutrition & Metabolism 2005: The effects of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet on the polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot study [weak evidence]

- In a 2015 study, 24 women with PCOS who ate diets containing roughly 70 grams of net carbs per day for 12 weeks had significant reductions in insulin levels, insulin resistance, TG, and testosterone, along with losing an average of 19 pounds (8.6 kg) by the end of the study:

Journal of Obesity & Weight Loss Therapy 2015: Low-starch/low-dairy diet results in successful treatment of obesity and co-morbidities linked to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) [weak evidence]

- A 2020 study showed 14 women with PCOS showed a significant improvement in hormone levels and markers of insulin resistance.

Journal of Translational Medicine 2020: Effects of a ketogenic diet in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome [nonrandomized study, weak evidence]

- Studies in 2006 and 2013 showed that even a very modest reduction in carbohydrates (from 55 to 41 percent of energy) can result in significant improvements in weight, hormones, and risk factors for women with PCOS:

Fertility & Sterility 2006: Role of diet in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome [weak evidence]

Clinical Endocrinology 2013: Favourable metabolic effects of a eucaloric lower‐carbohydrate diet in women with PCOS [weak evidence]

- Finally, a 2017 review of relevant studies notes that low-carbohydrate diets tend to "reduce circulating insulin levels, improve hormonal imbalance and resume ovulation to improve pregnancy rates."

Nutrients 2017: The effect of low-carbohydrate diets on fertility hormones and outcomes in overweight and obese women: a systematic review [systematic review of randomized and nonrandomized trials; weak evidence]

Beyond the scientific evidence cited above, the clinical experience of doctors using carbohydrate restricted diets strongly supports these diets as an effective treatment for PCOS:

How to reverse PCOS with low carb

Irritable bowel syndrome

In 2009, researchers examined a very low-carb diet (less than 20 grams of carbs a day) for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). During the study, 13 people with diarrhea-predominant IBS started with a standard American diet for two weeks, then switched to a very-low-carb diet for four weeks; 10 out of the 13 subjects (77%) had significant positive changes, with the very-low-carb diet reducing abdominal pain and diarrhea and improving their quality of life:

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2009: A very low-carbohydrate diet improves symptoms and quality of life in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome [weak evidence]

In recent years, much research has been done on a diet low in FODMAPs. FODMAP is an acronym for "fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharide's and polyols." That unwieldy name describes types of short-chain carbohydrates found in many fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains, dairy products and some processed foods. At least one study has shown that 75 per cent of people with diagnosed IBS had their symptoms improve on a low FODMAP diet.

European Journal of Nutrition 2016: Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis [moderate evidence]

Learn more about IBS and low carb

Inflammatory bowel disease

Anecdotal reports suggest that a low-carb or low-carb Paleo diet may reduce symptoms of inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohns' disease or ulcerative colitis.16

To our knowledge, there are not yet any controlled trials investigating whether carbohydrate restriction can improve inflammatory bowel disease. However, this published case report suggests that this is an area in need of further investigation:

International Journal of Case Reports and Images 2016: Crohn's disease successfully treated with the paleolithic ketogenic diet [very weak evidence]

Reflux disease / heartburn

At least two studies show that low-carb diets may be promising treatments for reflux disease.

In a small study of eight obese people with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), participants had esophageal pH tested before and after consuming a ketogenic diet containing less than 20 grams of carbs per day for six days. The second test showed normalization of esophageal pH levels, which indicates a less acidic environment in the esophagus. In addition, participants reported improvements in chest burning and discomfort, belching, and other symptoms of reflux.

Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2006: A very low-carbohydrate diet improves gastroesophageal reflux and its symptoms [weak evidence]

In another study, 42 obese women with GERD followed a low-carb, high-fat diet for 16 weeks. By week 10, all of these woman had a complete resolution of GERD symptoms and were able to discontinue their antacid medications.

Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2016: Dietary carbohydrate intake, insulin resistance and gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease: a pilot study in European‐ and African‐American obese women [weak evidence]

Learn more

Migraine

Is it possible to reduce or even completely eliminate migraines by reducing dietary carbohydrate? Studies and anecdotal evidence suggest it might be. There are at least two studies so far that show that carbohydrate restriction can help those who suffer from migraines:

- Euroupean Journal of Neurology 2015: Migraine improvement during short lasting ketogenesis: a proof-of-concept study [weak evidence]

- Journal of Headache and Pain 2016: Cortical functional correlates of responsiveness to short-lasting preventive intervention with ketogenic diet in migraine: a multimodal evoked potentials study [weak evidence]

Learn more about migraine and low carb

ADHD

Limited evidence from animal studies and case reports suggests that low-carb diets might be helpful for some people with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other related conditions, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and Tourette's syndrome.

Learn more

Alzheimer's disease

Two randomized controlled trials have found improvement in either memory or quality of life and daily activities in people with Alzheimer's and cognitive impairment who were using a ketogenic diet:

Alzheimer's Research and Therapy 2021: Randomized crossover trial of a modified ketogenic diet in Alzheimer's disease [moderate evidence]

Neurobiology of Aging 2012: Dietary ketosis enhances memory in mild cognitive impairment [moderate evidence]

An increasing number of case reports show the potential benefit of low-carb diets for treating Alzheimer's disease (AD):

Aging 2016: Reversal of cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease [very weak evidence]

Alzheimer's & Dementia: APOE ε4, the door to insulin-resistant dyslipidemia and brain fog? A case study [very weak evidence] Learn more

There are also studies linking high, or even "normal," non-diabetic blood sugar levels to dementia and AD. Because a ketogenic diet lowers blood glucose, it could conceivably cut the risk of developing these diseases. This study investigates this connection:

The New England Journal of Medicine 2013: Glucose levels and risk of dementia [very weak evidence]

Ketogenic diets provide ketones as an alternative fuel source for the brain, which may be of benefit to people with dementia or other cognitive issues. Clinical trials in patients with AD or cognitive impairment have shown that, even though the brains of these individuals can't use glucose effectively, they may have a similar capacity to use ketones as the brains of healthy older people:

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2016: Can ketones compensate for deteriorating brain glucose uptake during aging? Implications for the risk and treatment of Alzheimer's disease [overview article]

Learn more

Parkinson's disease

An eight-week RCT found that people with Parkinson's disease who ate a ketogenic diet had greater improvement in symptoms than those who ate a low-fat diet:

Movement Disorders 2018: Low‐fat versus ketogenic diet in parkinson's disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

The following small pilot study of five people with Parkinson's disease showed an improvement of symptoms on a ketogenic diet. There was no control group, so a placebo effect can't be ruled out:

Neurology 2005: Treatment of Parkinson disease with diet-induced hyperketonemia: a feasibility study [very weak evidence]

One RCT found exogenous ketone esters improved exercise time by 24% in patients with Parkinson's, suggesting ketones may have a metabolic benefit.

Frontiers in Neuroscience 2020: A ketone ester drink enhances endurance exercise performance in Parkinson's disease [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Otherwise, aside from a few case studies, there is not much more published research in this area.

Multiple sclerosis

Similar to research on Parkinson's disease, high-quality evidence for benefits of carbohydrate restriction in multiple sclerosis (MS) is extremely limited. Beyond occasional positive anecdotal reports, there is some emerging clinical research.

A 2015 study reported that MS patients who followed a ketogenic diet or fasted for several days experienced significant improvements in quality of life scores and TG levels:

European Committee For Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis 2015: Ketogenic diet and prolonged fasting improve health-related quality of life and lipid profiles in multiple sclerosis – a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

A small pilot study in 20 people with relapsing MS demonstrated lack of progression of their disease for 6-months while following a ketogenic diet. While this is preliminary data that needs larger confirmatory studies, it raises the possibility that a ketogenic diet might have a role in MS treatment:

Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation 2019: Pilot study of a ketogenic diet in relapsing-remitting MS [uncontrolled study; very weak evidence]

Fibromyalgia

Preliminary evidence suggests a connection between fibromyalgia and insulin resistance, high blood sugar, and type 2 diabetes. Since low-carb diets often are effective in treating the latter conditions, a positive effect on fibromyalgia could be possible. Learn more

PloS ONE: Is insulin resistance the cause of fibromyalgia? A preliminary report [very weak evidence]

Intermittent fasting

It's not unusual for people to combine a low-carb diet with intermittent fasting, either for convenience or to improve the effectiveness of weight loss or diabetes reversal.

A common variant of intermittent fasting, also called time restricted eating when it is for less than 24 hours, is called 16:8, meaning you fast for 16 hours per day and consume all of your daily food during an eight-hour window. This is often achieved by skipping breakfast. This can sometimes improve weight loss results.17

British Medical Journal 2019: Effect of breakfast on weight and energy intake: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

Intermittent fasting appears to be a promising alternative to continuous calorie restriction:

Translational Research 2014: Intermittent fasting vs daily calorie restriction for type 2 diabetes prevention: a review of human findings [overview article]

In addition, as little as 14 hours of fasting for 12 weeks appears to be enough to see significant metabolic improvements.

Cell Metabolism 2020: Ten-hour time-restricted eating reduces weight, blood pressure, and atherogenic lipids in patients with metabolic syndrome [observational study, weak evidence]

And a six-week trial in women over age 60 showed 16 hours of daily fasting improved weight loss and metabolic health.

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020: Effect of a six-week intermittent fasting intervention program on the composition of the human body in women over 60 years of age [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Learn more about intermittent fasting

Low carb and the environment

Low-carb diets are often described as being ecologically unsustainable, due to concerns about the impact of meat production on the environment. However, these concerns may be largely unfounded.

First of all, low-carb and keto diets are moderate in protein; they are not "high" protein diets. Protein as a percentage of calories may increase because carbohydrate calories are kept low, but this does not necessarily indicate an increase in amounts of absolute protein, or meat, intake. Recommendations for protein intake on carbohydrate restricted diets fall well within the acceptable macronutrient distribution ranges (AMDR) recommended by the U.S. government. 18 It's even possible to eat a vegetarian or vegan low-carb diet.

Secondly, the environmental impact of meat production is highly variable. Even the production of beef – usually considered by far the worst from a climate perspective – can be handled in an environmentally friendly way.

A 2018 study demonstrates that properly managed livestock can be made climate neutral or even carbon-negative, meaning more carbon is stored in soil than is released into the atmosphere:

Agricultural Systems 2018: Impacts of soil carbon sequestration on life cycle greenhouse gas emissions in Midwestern USA beef finishing systems [weak evidence]

Learn more: The green keto meat eater, part 1

Red meat and health

Warning are often raised regarding the negative health effects of red meat. However, these claims are supported only by weak nutrtional epidemiology studies, with low statistical associations and high possibility of confounding and bias. Most epidemiological findings like these turn out to be false when they are tested in intervention trials.19

Most recently, a review of RCTs comparing lower vs. higher red meat consumption used the GRADE system to quantify the strength of the evidence. The authors concluded that restricting red meat may have little or no effect on whether a person will develop heart disease or cancer.

Annals of Internal Medicine 2019: Effect of Lower Versus Higher Red Meat Intake on Cardiometabolic and Cancer Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

This same group of researchers showed that evidence from observational studies trials does not support dietary guidance to limit red meat consumption.

Annals of Internal Medicine 2019: Reduction of Red and Processed Meat Intake and Cancer Mortality and Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies. [meta-analysis of cohort studies; weak evidence]

Not surprisingly, when the theory that red meat causes cancer is tested in an interventional trial, it is not confirmed. A good example is the Polyp Prevention Trial, which tested a low-fat, low-meat diet versus usual diet on over 2,000 people for 8 years to see if it could prevent colorectal cancer. Although the experimental group changed their diets significantly, they did not have lower rates of cancer recurrence.

- Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2007: The polyp prevention trial continued follow-up study: no effect of a low-fat, high-fiber, high-fruit, and -vegetable diet on adenoma recurrence eight years after randomization [moderate evidence]

Another example is the Women's Health Initiative. Half of nearly 49,000 women were randomized to 8 years on a low-fat diet, with significantly less red meat. There was no reduction in colorectal cancer incidence (in fact, the non-significant trend was towards a slightly higher risk in the intervention group).20

- Journal of the American Medical Association 2006: Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of colorectal cancer [moderate evidence]

Learn more: Guide to red meat – is it healthy?

Diet and cancer: What we know and what we don't

Salt and health

In order to prevent heart disease, the American Heart Association recommends that everyone should restrict sodium intake to less than 1500 mg per day, which equals about 3/4 teaspoon of salt.

Yet, for individuals on a low-carb diet, sodium needs may actually increase, due to increased losses via the kidneys.21

As a result of these increased needs, individuals using low-carbohydrate diets are not typically asked to restrict sodium intake. Concerns have been raised about the safety of this practice for these individuals, many of whom may also belong to specific groups — such as African Americans or people with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or heart disease — for which very-low-sodium diets have been recommended in the past.

Although very-low-sodium diets may be beneficial for some individuals who are also on high-carb diets, it is difficult to determine if this is a reasonable concern for those who are on low-carb diets given that support for significant sodium reduction for all individuals is mixed.

In fact, a 2013 US Institute of Medicine report concluded that reducing sodium to very low levels is not recommended for the general population. The report also found that current science "provides some evidence for adverse health effects of low sodium intake" among individuals with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and heart disease.

In addition, a 2014 Cochrane review of RCTs that tested interventions to reduce sodium intake found no support for dietary advice to restrict salt intake:

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014: Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease [systematic review of RCTs; strong evidence]

Those reports stand in contrast to another review of RCTs that found reduced salt intake did improve lifespan and reduce deaths from heart disease:

Annals of Internal Medicine 2019: Effects of nutritional supplements and dietary interventions on cardiovascular outcomes: An umbrella review and evidence map [systematic review of RCTs; strong evidence]

The inconsistent data makes it difficult to draw strong conclusions or make definitive recommendations for the general population to significantly restrict sodium intake.

In addition to the two reports mentioned above, population-wide advice to cut salt intake to very low levels has also been brought into question by seven observational studies that show no links between very low salt intake and health benefits or longevity.

Although these studies do not show causality, they seem to indicate that intakes of sodium below about 3500 mg per day may be associated with a shorter lifespan, especially for older adults.

The studies

- European Heart Journal 2020: Sodium intake, life expectancy, and all-cause mortality [very weak evidence]

- Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2018: Association between sodium excretion and cardiovascular disease and mortality in the elderly: a cohort study [very weak evidence]

In this study in an elderly population, lower intakes of salt were associated with shorter lifespans. - Journal of the American Medical Association 2016: Sodium excretion and the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease [very weak evidence]

This study showed an increased risk of cardiovascular events for sodium intakes above about 4000 mg per day in people with mild to moderate kidney disease. People with kidney disease may be more sensitive to higher salt intakes, but very low intakes were not associated with increased health benefits. - Lancet 2016: Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled analysis of data from four studies [very weak evidence]

This study shows, on the one hand, consuming more than 7000 mg of sodium per day was associated with increased risk of heart attack and premature death in people with hypertension. On the other hand, consuming less than 3000 mg of sodium per day was associated with increased risk in both people with normal blood pressure and those with hypertension. - Journal of the American Medical Association 2011: Fatal and nonfatal outcomes, incidence of hypertension, and blood pressure changes in relation to urinary sodium excretion [very weak evidence]

Overall, this study suggests that lower sodium intake is associated with increased risk of death from heart disease. - Diabetes Care 2011: Dietary salt intake and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes [very weak evidence]

In a population of people with type 2 diabetes, higher sodium intakes were associated with decreased risk of premature death from all causes and from death from heart disease. - Diabetes Care 2011: The association between dietary sodium intake, ESRD, and all-cause mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes [very weak evidence]

In this study in people with type 1 diabetes, both highest and lowest intakes of sodium were associated with increased mortality. Furthermore, individuals with the lowest sodium intake had the highest risk of end-stage kidney disease. - Hypertension 1995: Low urinary sodium is associated with greater risk of myocardial infarction among treated hypertensive men [weak evidence]

As the title of the study indicates, low intakes of sodium were associated with greater risk of heart attacks in men being treated for high blood pressure. This effect was largest in the group of men over 55 years old.

A comprehensive guide to salt

Learn more about salt intake, other electrolytes, and a low-carb diet

External resources about the science of low carb

Virta Health: A comprehensive list of low-carb research

Public Health Collaboration UK: Randomised controlled trials comparing low-carb diets to low-fat diets

The science of low carb

MEMBERS ONLY

Dr. William Yancy, a researcher who investigates the effects of carbohydrate-restricted diets, shares his views on the science of low carb.

More

Improve this page

Do you have a suggestion – big or small – to improve this page? Anything that you'd like added or changed? E-mail me at andreas@dietdoctor.com.

Source: https://www.dietdoctor.com/low-carb/science

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar